LifeWay Research released the results of an updated study exploring U.S. Protestant pastors’ experiences with mental illness and the support their churches offer to affected individuals and families. The phone survey of 1,000 Protestant pastors was conducted in September, 2021 using identical methodology to an earlier study they conducted in May, 2014. The study might be viewed as one measuring stick of the impact of the mental health ministry movement, and is a decidedly “mixed bag” Let’s rip into the “bag” for a look at the good, the bad, the ugly and the delusionally inaccurate observations reported from the study.

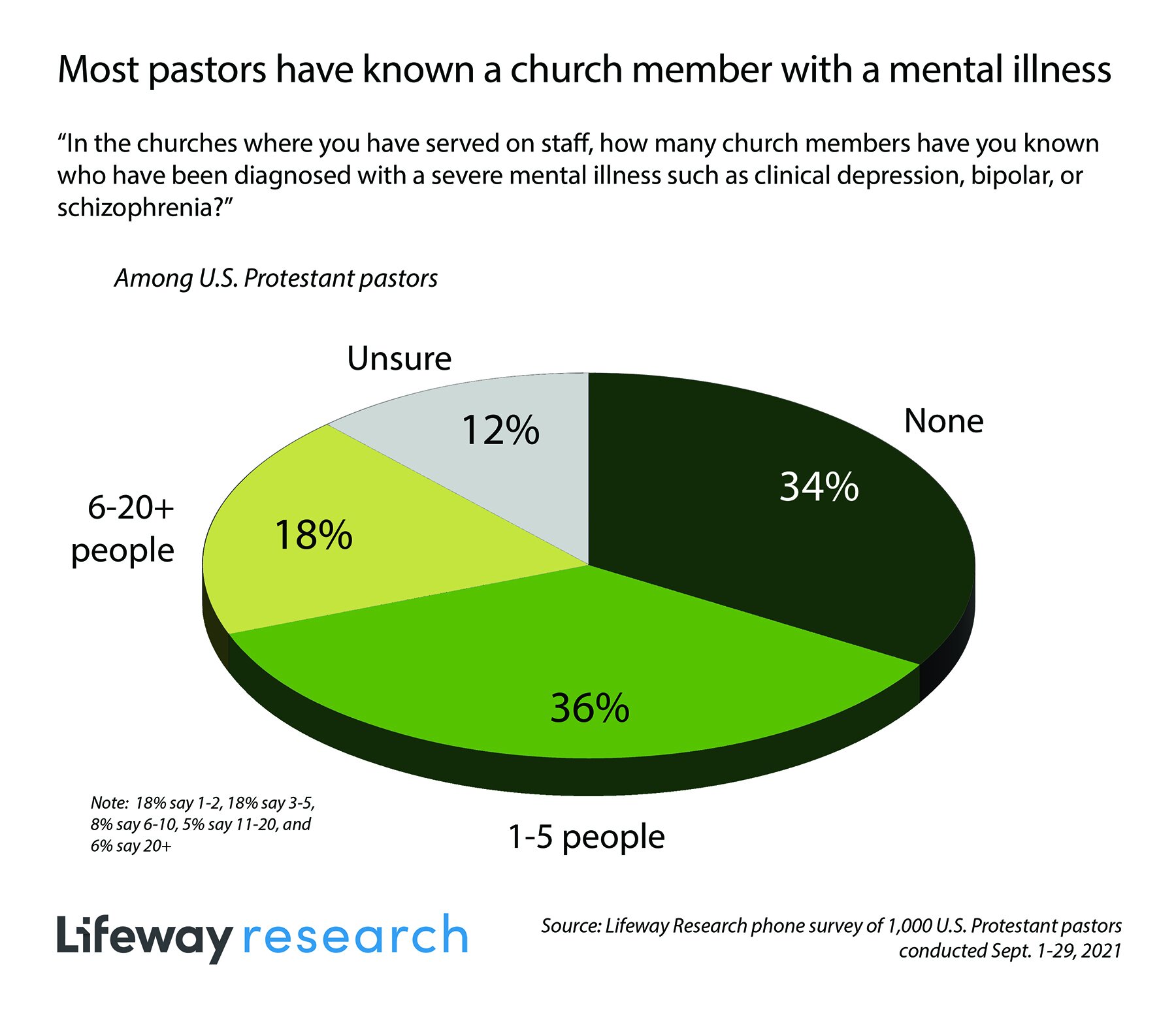

A shocking number of pastors continue to report having had little or no contact with persons with serious mental illness - major depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Persons affected by these conditions represent at least 5% of the adult population in the U.S. If a pastor can work in a church for any length of time without getting to know someone with a serious mental illness, persons with those conditions are either reluctant to talk about their mental health or extremely underrepresented in the congregation.

We’re making some progress in getting pastors to talk about mental illness from the pulpit. Nearly half of the pastors surveyed in 2014 reported they rarely or never discussed mental health concerns in their sermons. That number has been reduced to 37%. This is a key issue - in a survey LifeWay conducted around the time of the 2014 pastor survey, the most common answer reported by family members of adults with serious mental illness when asked what their church could do that would be most helpful was for their pastors to talk about mental health concerns during worship services.

The most dramatic change between the 2014 and 2021 surveys is the number of pastors who report having been formally diagnosed with a mental health condition - a 42% increase over the seven year period. Given the challenges that pastors have experienced during COVID, I was surprised the percentage of pastors with personal experience of mental illness wasn’t significantly higher.

Pastors feel marginally more prepared to identify persons with mental health concerns in their churches and refer them for help.

Fewer pastors feel strongly about the need to support attendees with mental health concerns now when compared to 2014. I suspect church leaders have so many needs to address at this time (getting their congregations back to worship services, for one) that supporting families with mental health concerns isn’t high on their priority list.

Some additional observations from the study…

Younger pastors appear to have a greater awareness of, and sensitivity to mental health needs. Compared to pastors ages 45 and up:

Younger pastors appear to have a greater awareness of, and sensitivity to mental health needs.

Younger pastors are more likely to speak openly about mental illness from the pulpit several times a year or more.

Younger pastors are more likely to report that their churches have current mental health referral lists and plans for supporting families impacted by mental illness.

Younger pastors are likely to report feeling equipped to refer attendees for mental health support.

I’d hypothesize the increased awareness and sensitivity among younger pastors comes from spending their formative years in a time when rates of mental illness exploded. I’d like to think our seminaries are doing a better job at training young pastors on mental health concerns, but this study from Baylor University and this report suggest seminary students get very little formal training on mental health concerns.

The more theologically conservative the church, the less likely pastors are to be aware and supportive of mental health needs. Pastors from non-denominational churches (83%) are less likely than Methodist pastors (93%) to endorse the importance of mental health support from the church and more likely to deny feeling equipped (19%) to make mental health referrals than Pentecostal pastors (6%).

Awareness - and support is likely to be greater at larger churches. The larger the church, the more likely their pastor report having plans to support family members of the mentally ill, offer professional counseling, groups such as Celebrate Recovery and educational programs on topics such as anxiety or depression.

I would start to call into question the reality testing of the pastors surveyed based upon their claims to have plans to support the mental health of persons affected in the church and their families. I can’t help but think most pastors want to believe their churches have a plan to help. 40% of the pastors surveyed claim their churches have a plan. In our experience, I would guess that less than 1% of churches could truly be described as “mental health-friendly” churches.

Where is the impetus for mental health ministry going to come from within the church? Given the situation the American church finds itself in post-COVID, the impetus will largely need to come from “non-professional Christians” - mature believers who are active and involved in local churches who may not have a seminary degree or a staff position at a church but do have a sense of calling or firsthand experience of the impact of mental illness. Mental health support may largely be a ministry initiated by the people of the church, with an identification with a local church in situations where the local church leadership is encouraging and supportive. What might this look like?

It might look like a Christian-based mental health support group organized by a couple or family who approach the leadership of their church about accessing space for meeting or promoting the group. Fresh Hope is open to training facilitators for groups operating independently of local churches and provides resources for approaching church leaders about group sponsorship.

It might look like an individual or small group committing to provide respite care for families in their homes or volunteering to provide meals for families when a child or adult is experiencing a mental health crisis.

It might look like someone volunteering to serve as a mental health liaison within their church.

It might look like a mental health professional, or a person impacted by mental illness reaching out to their pastor to share the research examining the impact of mental health communications on people both inside and outside of the church.

One takeaway I had from the new LifeWay study is that we can’t wait for pastors to “fix” this problem. If the Holy Spirit is leading you to become active in mental health ministry regardless of whether or not you’re a pastor or on church staff, our team would love to come alongside you and resource you in any way we can. Reach out to Catherine Boyle, our mental health ministry director if you’re ready to take the next step.